Have you heard about those IQ tests private and exclusive schools require your child take for entering kindergarten? Well neuroscientists have shown that the tests will give false results 73% of the time[1]… not a good score considering your child’s future is on the line. Your child’s capacity for self-control and motivation are better indicators of your child’s potential [2].

“There are a set of skills that children need to be learners. They need to be able to pay attention, to concentrate, to focus for long periods of time.[3]” – Dr. Pamela Cantor, founder of Turnaround for Children

Self-control and motivation are part of a set of skills known as the executive functions that develop in the frontal cortex of the brain and is unique to humans; it is what separates us from our cousins, the apes. To be alert, to plan, to organize, make strategies, solve problems, use short-term memory, to schedule in time and space – all are resolved in the frontal cortex in the brain. This is also where this information is passed on to other important brain areas and their functions “so that behavior can be guided by our accumulated knowledge”[4]. So if you are looking for an indication of your child’s progress in developing his or her brain, you are better to look at their self-control and motivation than their IQ on an exam.

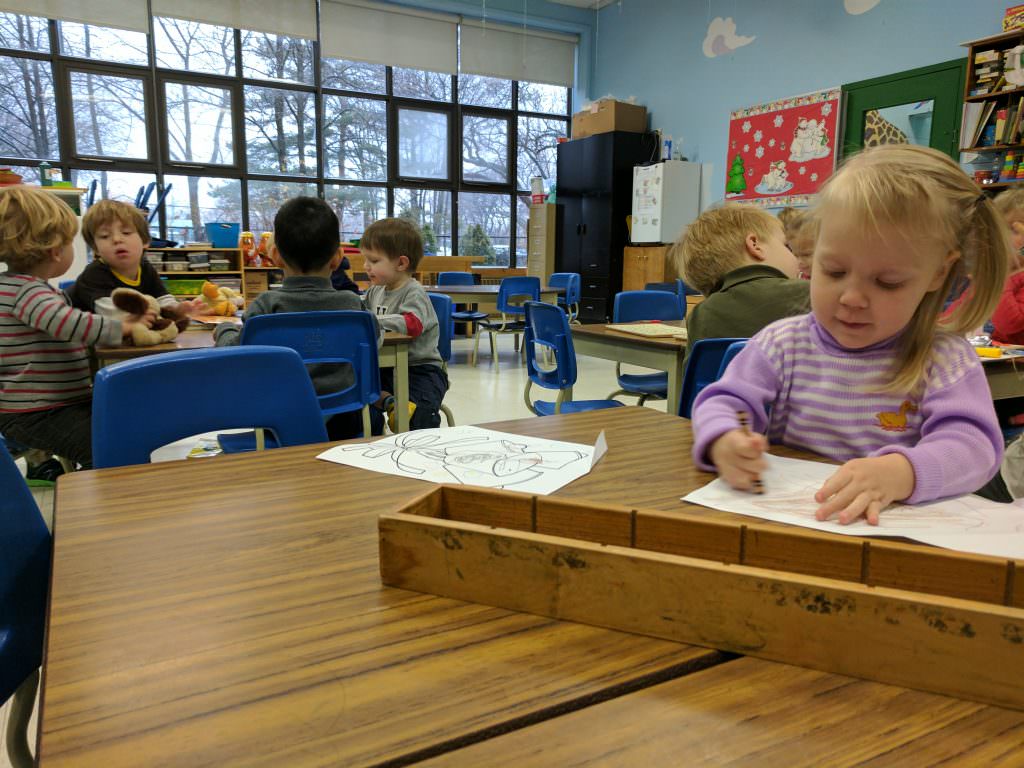

Examples of Success

Thankfully we are able to encourage the development of executive functions. Two curriculums in particular, Vygotsky and Montessori, I will describe here to show to be particularly efficient than others at the pre-school level.

“Tools of the Mind” is a program based on a curriculum created by Russian scholar Vygotsky (1896-1934). Children who participated in this pre-school programs in the United States have shown higher scores of executive function development than their peers in traditional schools[5], as well as better overall behavior and academic success [6]. This method encourages children to play out real-life scenarios over a relatively long duration while staying in character, such as playing doctor or architect. It prioritizes games such as Simon Says that require long periods of concentration and focus and memory. This curriculum will also teach specific tools, such as to have children use their voice to guide themselves during a particularly difficult task, or to memorize a new rule. Physical tools, such as a drawing of an ear, will help children to focus on hearing.

Montessori’s methods focus on what’s called normalization, which is to help children “shift from disorder, impulsivity, and inattention to self-discipline, independence, orderliness, and peacefulness”[7]. For example, children have the choice between different games to stay engaged, motivated and curious. Activities are designed in such a way that the children can realize their own mistakes by being critical of their own behavior, and correct it. In other words, if a child must wait to engage with a particular table’s activity, they learn patience.

In both approaches Vygotsky and Montessori, teachers are asked to adjust the difficulty of their activities in order to optimize their students’ learning.

Another example of a method designed to develop executive functions is found in a study made by Dr. Eric Pakulak and his Brain Development Lab at the university of Oregon. They followed the level of attention of preschoolers in the Local Headstart program in Eugene, Oregon. Through activities designed to have the children concentrate and ignore stimuli, and to encourage what’s known as “positive parenting”, these children improved their concentration.

“What we were able to show is that children who were randomly assigned to receive this intervention that involved working more closely with parents as well as the child attention training, that we do see that these brain systems for attention improve in children from backgrounds of poverty.[8]” – Dr. Eric Pakulak

The science is clear, self-control must be developed in preschoolers at school and at home to prepare them for learning. To concentrate, to be motivated, and control one’s impulses, to remember in the short-term – everything that is linked to the executive functions – are skills that give your child a solid base from which to expand on his or her potential, to find goals and to realize their dreams.

Strategies and tactics to develop the executive functions of your child

Children now at seven years old have a similar capacity of self-control as the five year-olds of 1940[9]. According to the researchers, this due to a depreciation in quality and quantity of games available to preschoolers. It is too easy now to believe that television programs may teach, but they do not leave place to your child’s own imagination. Thankfully, it is easy and cheap to fix this issue now that it has been identified.

To make-believe (scenarios)

In a toy box, the colored tissues and building blocks of all shapes and sizes permit children to discover limitless scenarios to make-believe. They could find a cape of a superhero, or the dress of a princess, a picnic cloth or some sort of hammer, all created from their imagination. What’s best if there are friends of different ages to help, and an environment without distractions and at least thirty minutes of time to play.

For the scenario to be a rich learning experience, it is important for your child to do more than a single, repetitive task, such as chopping vegetables, or hammering on nails. There must be a story that can progress. This is why it is important to develop the scenario before it begins, and this is where the older kids (you included) can help. How many characters will there be? Who will play who? The children noted in research in Tools of the Mind planned out their characters on paper to the best of their skills. If they come out of character during the scenario, teachers would ask the child to return to their paper as to remember their character so they may return to make-believe.

You could, for example:

- Suggest ideas for make-believe based on real-world experiences. Reading a bed-time story, visiting the dentist, or taking the bus, are all sources of inspiration.

- Take your child to visit a fire station, and get them to ask questions to the firemen and women about what they do in case of a fire. This will give your child new ideas for their later scenario.

- At a restaurant, make your child pay attention to what questions you ask the waiter, and what they do while they take your order and how they behave afterward.

- Bring together the needed accessories available to you for the scenario of your child’s choosing that are safe and fun with which to pretend. These accessories will help your child take hold of their character and stay focused on their goal.

- Referee any disputes. Keep a coin handy to flip to resolve simple matters, and encourage the children to vocalize their emotions using sentences such as “I feel ________” and “I do not like when _________”. The idea is to intervene as least as possible while promoting a rich learning environment. If you must intervene, it is better to ask questions than to offer suggestions. You may mask your suggestions questions (“Are you about to prepare your customer’s bill?”).

Children are better able to remember and to show restraint when the rules of the activity are repeated right before they begin each time you play [10]. You cannot expect them to remember everything, so repeat the rules. “It’s carpet time! We stay on the… carpet! We use our… inside voices! What do we do with the toys? We… share!” No matter if it’s a game, dinner-time or anything else, to remind your child of the rules is never wasted, and is best done right before they need to apply them.

Other games

Games which are beneficial for the development of executive functions should have some or all of these characteristics:

- The child should stay concentrated and keep in mind the rules. Then if the rules change throughout the game, then the child must control their impulsivity and remember the new rule, which is a marker of self-control.

- Children should ignore distractions and focus on a particular task.

- Children should remember the position of an object or repeat words that have just been said. This works their short-term memory.

- The child should plan out a strategy or plan before they act.

These are some examples of games that employ these strategies:

- Simon Says – Children are asked to listen to commands and perform them only if the leader (Simon) says “Simon Says” before the command. If the command is “Simon says to touch your feet”, then the children must touch their feet. If the command is “Touch your head” or “Marco says to touch your head”, then they must not touch heads. The children must exercise self-control and impulsivity in order to successfully play the game.

- Red Light, Green Light – At the beginning of the game the teacher and children are separated by a large distance. When the teacher shouts “green light!”, the children advance toward the teacher, and when “red light!” is said, they must stop. The game asks the children be concentrated and alert and to respond and control their bodies according to rules. Then you change the rules. Green becomes stop, red means to make a funny face, and purple is to go. This will challenge the short-term memory and self-control of the children to respond properly to the new environment and conditions.

- Building Blocks – Children can collaborate on planning out a construction project and build it in teams. This requires the children to work on their self-control, as building the blocks in an unstable way will make their projects collapse. Planning and coordination of efforts are important to seeing success.

- Story time – Telling stories develops language skills, creativity, memory, logic and self-control. [11]

- Hopscotch – The rules of the game change based on the placement of a rock within a grid of numbered squares written in chalk on the asphalt. If the children waiting their turn clap their hands or sing, then then game will require concentration and focus to perform throughout the distractions.

- Obstacle Course with Distractions – For example, the child must carry a marble on a spoon while keeping step on a length of yarn – all the while, their friends are drumming their hands on the ground!

- Find the Mistakes – The game, often found in print media like newspapers, is to look at a copy of an image that’s been altered in subtle ways. The child will develop their executive functions because they must analyze, critique and make decisions.

At school, like at home, it is easy and fun for children to develop their frontal cortex and executive functions. More than just games, and environment where children feel secure and feel little stress will help them develop. By offering these conditions and targeted games, you will help develop key competencies for your child’s future academic and professional success. These skills will follow them their whole lives, and will be the tools they need to realize their dreams.

Footnotes

[1] Bronson, P., et Merryman, A. (2009). NurtureShock : New Thinking About Children p.93

[2] Bronson, P., et Merryman, A. (2009). NurtureShock : New Thinking About Children p.174

[3] Bertelsen, P. et Teeling, J. (2016). School of the future. [Documentaire]. États-Unis : Nova.

[4] Galinsky, E. (2010). Mind In The Making : The Seven Essential Life Skills Every Child Needs p.15.

[5] Bronson, P., et Merryman, A. (2009). Ibid. p.170

[6] They also had superior results at the standardized test of their state. Their average score was 21 point percentile higher then the other kids of New Jersey on the national spectrum (86th percentile compared to 65th).

[7] « Normalization is a shift from disorder, impulsivity, and inattention to self-discipline, independence, orderliness, and peacefulness. » – Diamond A. et Lee K. (2011) Interventions Shown to Aid Executive Function Development in Children 4 to 12 Years Old. Science, 333. 959-964. Récupéré de http://science.sciencemag.org/content/suppl/2011/08/17/333.6045.959.DC1

[8] Bertelsen, P. (September 14th, 2016) NOVA:School of the future. [Documentary]. Boston : WGBH Boston. 18min56seconds

[9] Bodrova, E. et J. Leong, D. (2007). Tools of the mind : The Vygotskian Approach to Early Childhood Education, Second Edition. p.144

[10] Munakata, Y. et Barker, J. (2015). Time Isn’t of the Essence: Activating Goals Rather Than Imposing Delays Improves Inhibitory Control in Children. Récupéré de :

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/283576217_Time_Isn’t_of_the_Essence_Activating_Goals_Rather_Than_Imposing_Delays_Improves_Inhibitory_Control_in_Children

[11] Bodrova, E. et J. Leong, D. (2007). Tools of the mind : The Vygotskian Approach to Early Childhood Education, Second Edition. New Jersey : Pearson Education. p.155